Okay, here’s a short art history lesson. During the Renaissance and through to the Romantic period, painters opted to recreate natural reality rather than the more stylized paintings of the Byzantines before them. This meant using linear perspective, correct anatomical proportions, and blending brush strokes to draw as much verisimilitude out of a painting as possible.

However, as the Romantic age brought both technological and cultural advancements, painters shifted away from hyperrealistic paintings to more abstract depictions of the world around them. No longer were they concerned with blending brushstrokes to hide their hand’s work, but rather the raw visual effect of the whole piece.

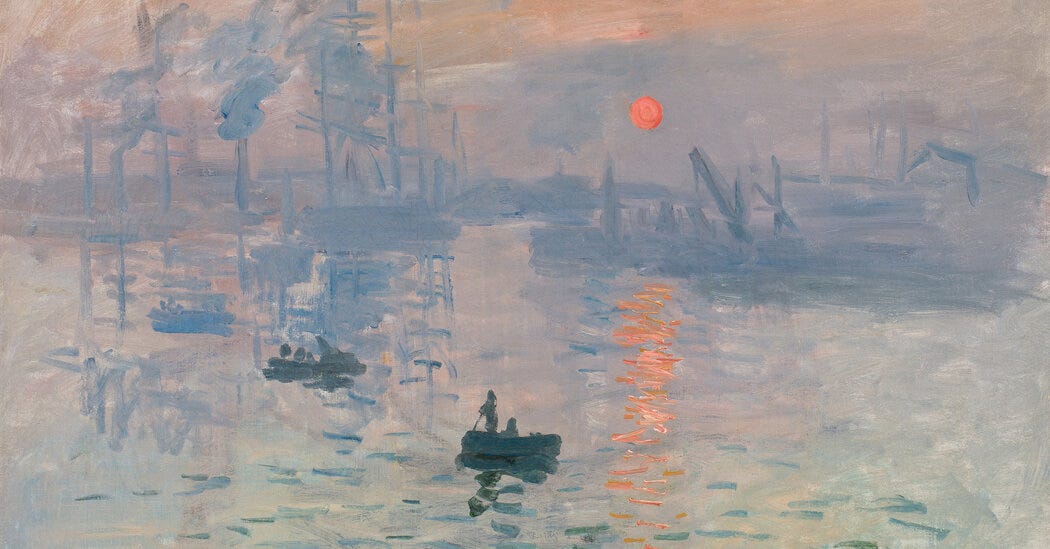

Take Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise for example. Up close, the orange streaks on the water appear chaotic, mere scribbles with no discernible meaning. Yet, when viewed from a distance, they form a reflection of the sun rippling across the harbor at dawn. The individual strokes merge into something greater than their parts, shaping a scene that feels more emotionally resonant than photographically accurate.

This phenomenon mirrors the way conspiracy theories function. Each lie within a theory, when scrutinized on its own, can be debunked. But when taken together, the lies create an overarching impression that is difficult to shake. Consider the most widely believed conspiracy theory: that Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Decades of investigation have systematically dismantled many of the supposed pieces of evidence for a larger plot, yet the lingering impression remains—how could a lone gunman have altered the course of history so dramatically? The sheer weight of the story overpowers the logic of individual facts. Like an Impressionist painting, a conspiracy theory’s power lies not in the precision of its elements but in the broader image they create, one that feels more compelling than reality itself.

The Impressionist model of truth—where individual details may be misleading or imprecise, yet collectively form a compelling and persuasive image—offers a useful framework for understanding both conspiracy theories and broader patterns of misinformation.

In the movements that followed—Post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism—artists began to actively distort reality rather than merely suggest it, deconstructing form and perspective to challenge the very idea of a singular, objective viewpoint.

Take Cubism, for example, which breaks an image into multiple perspectives at once, forcing the viewer to piece together a reality that is inherently unstable. This is strikingly similar to modern disinformation tactics, where contradictory narratives exist simultaneously—Trump is both a victim and a mastermind, Biden is both senile and dangerously cunning—leaving people unable to reconcile the pieces into a coherent whole.

Meanwhile, Surrealism, which sought to tap into the unconscious and present dreamlike distortions as reality, mirrors the emotional, almost mythic appeal of conspiracy theories. The stories they tell are not meant to be rationally consistent but to feel intuitively true on a deeper, almost subconscious level.

In this sense, misinformation today does not just operate like an Impressionist painting, subtly shaping an overall impression—it now functions more like a Cubist or Surrealist masterpiece, where reality is fractured, and the viewer is left to construct their own version of the truth from scattered and manipulated fragments.

Continuing the theme of open brushstrokes, let’s take a moment to examine a larger painting that’s nearing completion. It’s an open secret that the Russian model of disinformation doesn’t aim to construct a clear alternative reality but to muddy the waters, making every version of events seem equally plausible. You don’t need to convince people that Vladimir Putin is an upstanding leader—you just need to create enough doubt that the average citizen shrugs and thinks, Sure, he’s corrupt, but so is every politician.

The MAGA propaganda strategy follows a similar path. By accusing political opponents of every conceivable wrongdoing—credible or not—it enables the ever-powerful playground defense: Yeah, but they did it first. This overlaps with what Dave Chappelle famously described as the “honest liar” phenomenon: Trump may be guilty, but at least he’s honest about it, unlike those hypocritical Democrats.

The political and media landscape has shifted dramatically in the month and a half since Trump’s return to power. With threats of both trade wars and real wars, global trust in the U.S. as a stable ally has once again been shaken. Since inauguration, Trump has directly or indirectly threatened to take control of:

Panama

Canada

Greenland

The Gaza Strip

Instead of debating whether he’s serious—an approach the media took during his first term, culminating in a violent insurrection—let’s recognize the larger pattern rather than getting fixated on individual brushstrokes. Whether or not he had the largest inauguration crowd in history was irrelevant; what mattered was that a significant portion of Americans were being drawn into an alternate reality.

One of the ongoing “paintings” of this administration seems to be an extension of the “honest liar” strategy—this time, on a national scale. It’s no secret that the U.S. has the military and economic power to strong-arm smaller nations, but for decades, it was considered a diplomatic faux pas to openly admit it. America’s greatest foreign policy failures—Vietnam, Iraq—remain stains on its reputation because they violated the expectation that the U.S. would wield its power with restraint. But expectations can be rewritten. If brute force becomes the new norm, there’s no longer a need for pretense.

Taking a page from Henry Kissinger, it appears the MAGA movement is embracing a form of realpolitik. Unlike Kissinger, however, their focus isn’t regional stability but pure nationalism. What we are witnessing is not just a political strategy but a fundamental transformation in how power justifies itself. The United States, once invested in maintaining the illusion of moral authority, is now led by an administration that sees no need for pretense. If this is the new painting being created, the question is no longer whether each individual brushstroke is true or false, but whether anyone will be able to step back and see the full picture before it is complete.